2018.05 Low Carb and Low Carbon – Ted Eytan MD-1001 1096 – (View on Flickr.com)

2018.05 Low Carb and Low Carbon – Ted Eytan MD-1001 1096 – (View on Flickr.com)It’s research like this that makes nutrition guidance unusable.

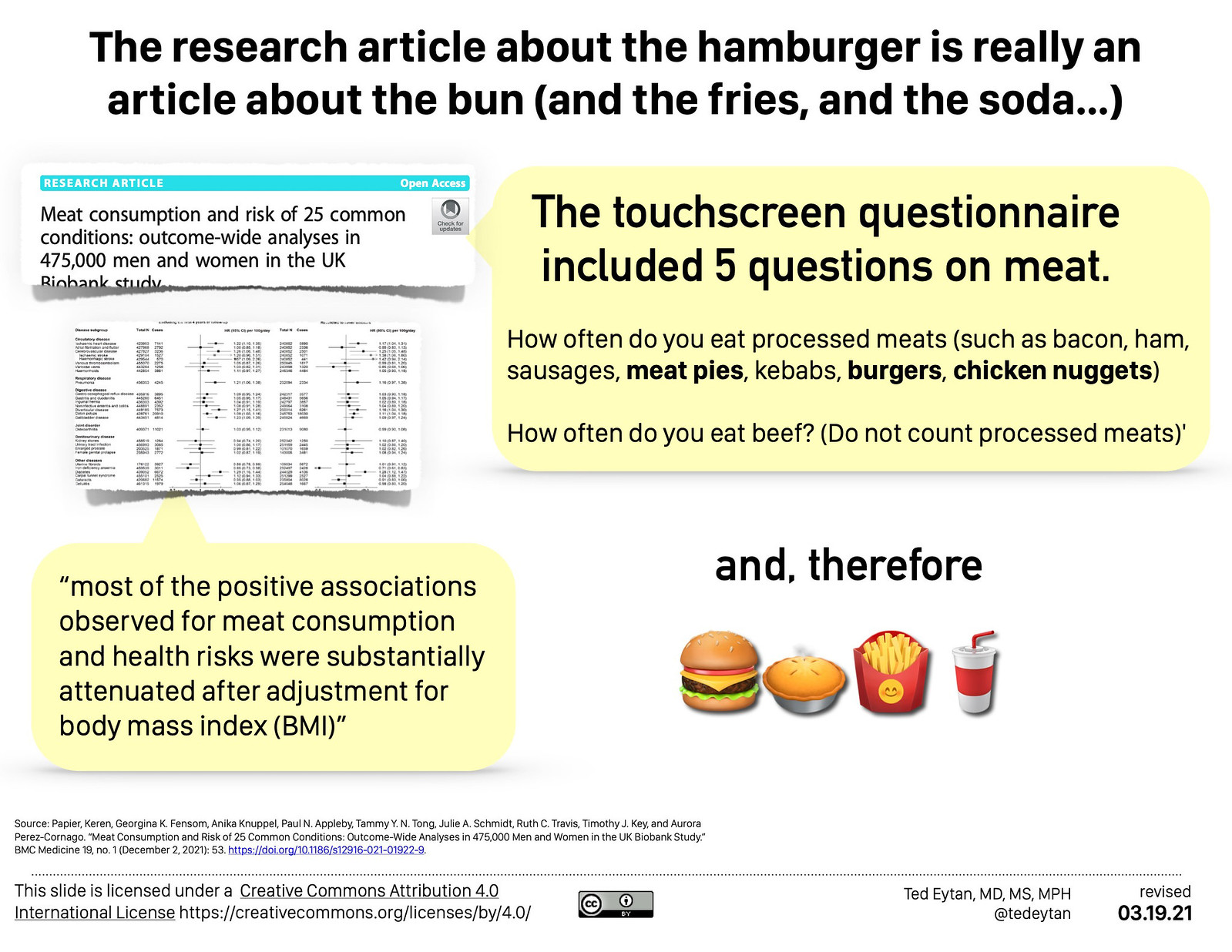

This article, purporting to show an association (not causation) between intake of meat products and disease, (a) demonstrates that the significant association is with BMI and (b) likely, the association is with what’s eaten with meat products, like, for example, french fries, buns, sodas etc. There are numerous other methodological problems with this study that make its findings unreliable/unusable for guiding health decisions.

Beyond the article itself, this is a reminder on strategies to understand research findings, even when they are published in peer-reviewed literature.

- Read the article. The whole thing, not the abstract.

- Understand potential financial and intellectual conflicts of interest. Know who paid for the research and the researchers.

- Read the supplemental material – this is often where researchers stash details that negate their own findings.

- Ignore the article title, sometimes it is not written by the researchers themselves and therefore is not a summary of what the article shows

This piece suffers from problems in all of the above areas.

How “meat intake” was assessed

A quick trip to the supplemental materials reveals the following

The touchscreen questionnaire included 5 questions on meat. These included the following: ‘How often do you eat processed meats (such as bacon, ham, sausages, meat pies, kebabs, burgers, chicken nuggets)’, ‘How often do you eat chicken, turkey or other poultry? (Do not count processed meats)’, ‘How often do you eat beef? (Do not count processed meats)’, ‘How often do you eat lamb/mutton? (Do not count processed meats)’ and ‘How often do you eat pork? (Do not count processed meats such as bacon or ham)’. We converted the responses to each of the five questions on meat into weekly intake equivalents as follows: 0, 0.5, 1, 3, 5.5 and 7 times per week.Papier, Keren, Georgina K. Fensom, Anika Knuppel, Paul N. Appleby, Tammy Y. N. Tong, Julie A. Schmidt, Ruth C. Travis, Timothy J. Key, and Aurora Perez-Cornago. “Meat Consumption and Risk of 25 Common Conditions: Outcome-Wide Analyses in 475,000 Men and Women in the UK Biobank Study.” BMC Medicine 19, no. 1 (December 2, 2021): 53. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-021-01922-9

Meat pies?

The characteristics of the people in the meat eating group

This information is not in the supplemental material, it’s very available in the body of the paper. People in the meat-eating group are much more likely to smoke, be overweight, exercise less, drink more, have lower educational status and other factors associated with a “less healthy lifestyle” which may include receiving appropriate preventive health interventions and other activities not accounted for. This is not a study of people who are healthy and eating meat in the context of a whole food diet.

While the researchers did control for some of these things epidemiologically, there is no escaping the likely presence of healthy-user bias, which I’ve written about previously and is well described (see: Just Read: Healthy User Bias: Statin Adherence and Risk of Accidents)

The actual results

This study, of a cohort from the UK Biobank, has used techniques previously that cloud the interpretation of data, such as combining the effects of eating processed and unprocessed meat (even when asked as above). In addition, many of the results do not have biological plausibility, for example, an analysis of meat eating among people who have never smoked shows a lesser association with pneumonia than with people who have smoked. The same goes for the analyses on poultry compared to meat. There are too many inconsistencies to go into here (happy to in the comments, though).

In any event, the researchers reveal these associations have a key confounder:

most of the positive associations observed for meat consumption and health risks were substantially attenuated after adjustment for body mass index (BMI)Papier, Keren, Georgina K. Fensom, Anika Knuppel, Paul N. Appleby, Tammy Y. N. Tong, Julie A. Schmidt, Ruth C. Travis, Timothy J. Key, and Aurora Perez-Cornago. “Meat Consumption and Risk of 25 Common Conditions: Outcome-Wide Analyses in 475,000 Men and Women in the UK Biobank Study.” BMC Medicine 19, no. 1 (December 2, 2021): 53. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-021-01922-9

In other words, when weight is taken out of the picture, the associations shown are much less strong. The authors attempt to tie weight to meat eating habits, but again, if what is eaten with the meat cannot be excluded, then this assertion is…. meaningless

Who paid for the research

Conflict of interest, both intellectual and financial, are a terrible problem in research, and especially nutrition research. I’ve compiled some of the most egregious examples (see: Disclosure/Conflict of Interest Statements updated/reaffirmed)

In the case of this research, it was funded by Wellcome Trust, which has known ties to groups advocating for plant-based nutrition (here’s an example). I always take the time to google the organizations listed to see what types of work they are underwriting

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, Our Planet Our Health (Livestock, Environment and People – LEAP) [grant number 205212/Z/16/Z]; Cancer Research UK [grant numbers C8211/A19170 and C8211/A29017]; and the UK Medical Research Council [grant number MR/M012190/1]. AP-C is supported by a Cancer Research UK Population Research Fellowship [grant number C60192/A28516] and by the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF UK), as part of the WCRF International grant programme [grant number 2019/1953].Papier, Keren, Georgina K. Fensom, Anika Knuppel, Paul N. Appleby, Tammy Y. N. Tong, Julie A. Schmidt, Ruth C. Travis, Timothy J. Key, and Aurora Perez-Cornago. “Meat Consumption and Risk of 25 Common Conditions: Outcome-Wide Analyses in 475,000 Men and Women in the UK Biobank Study.” BMC Medicine 19, no. 1 (December 2, 2021): 53. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-021-01922-9

Where to get better information

- For association type studies, I recommend the PURE study, which I’ve written about previously.

- For a comprehensive review of meat intake and health, the NUTRIrecs study findings have yet to be disproven, and still hold (despite intensive lobbying and unethical behavior by people and organizations promoting a different world view – see Backlash Over Meat Dietary Recommendations Raises Questions About Corporate Ties to Nutrition Scientists | Guidelines | JAMA | JAMA Network)

Reference

Papier, Keren, Georgina K. Fensom, Anika Knuppel, Paul N. Appleby, Tammy Y. N. Tong, Julie A. Schmidt, Ruth C. Travis, Timothy J. Key, and Aurora Perez-Cornago. “Meat Consumption and Risk of 25 Common Conditions: Outcome-Wide Analyses in 475,000 Men and Women in the UK Biobank Study.” BMC Medicine 19, no. 1 (December 2, 2021): 53. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-021-01922-9

1 Comment

[…] Just Read: When the research article about the hamburger is really an article about the bun (and the… […]