In many, if not all, of the sites we visited, the question of disparate access to PCHIT was raised. The same question has been raised with regard to EHR’s as well. In its report, the Expert Consensus Panel (see Electronic Health Records Still Not Routine Part of Medial Practice, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 3:27):

(The Expert Consensus Panel) has identified racial and ethnic minority patients and low-income or publicly insured patients as the two highest priority patient populations

The PCHIT Initiative broadens this view of vulnerable populations to include those with documented disparities including but not limited to individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. An additional vulnerable population of interest are returning soldiers (see: Longitudinal Assessment of Mental Health Problems Among Active and Reserve Component Soldiers Returning From the Iraq War).

Available data about Internet access contradicts conventional wisdom

Charts: Click on any to see full size (Sources: Benchmarking Digital Inclusion, ITIF, and Estabrook L, Witt E, Rainie L. Information Searches that solve problems. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2007)

In a review of the literature related to Internet use among vulnerable populations, we discovered that commonly held beliefs about use and access are not true. Even at the lowest educational and income levels, Internet use approaches 60 %, where it was only 10-30 % in 2001.

The following studies shed additional light on this issue:

- Estabrook L, Witt E, Rainie L. Information Searches that solve problems. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2007. A random sample survey performed between June and September, 2007 shows gains in Internet access and explores type of access – “High” for broadband at home or work, “Low” for no access or Dial-up only

- McNeill HL, Puleo E, Bennett GG, Emmons MK. Exploring Social Contextual Correlates of Computer Ownership and Frequency of Use Among Urban, Low-Income, Public Housing Adult Residents. J Med Internet Res 2007;9:e35. – In Boston public housing, 51 % of adults own and 42 % of adults regularly use computers, and those reporting feeling “safe” in their neighborhoods have a greater likelihood (76 % higher association) of using a computer regularly.

- Beckjord BE, Finney Rutten JL, Squiers L, et al. Use of the Internet to Communicate with Health Care Providers in the United States: Estimates from the 2003 and 2005 Health Information National Trends Surveys (HINTS). J Med Internet Res 2007;9:e20 – “In 2003, Internet users with high levels of education were more likely to have communicated online with an health care provider, consistent with previous studies. That education was nonsignificant in 2005 may suggest that health care consumers’ level of education is less of a barrier to communicating online with health care providers as the prevalence of online patient-provider communication increases.” and “We did not observe associations between online communication with health care providers and characteristics such as race/ethnicity or annual income that have been documented in other studies as evidence of a “digital divide””

- Carroll AE, Zimmerman FJ, Rivara FP, Ebel BE, Christakis DA. Perceptions about computers and the internet in a pediatric clinic population. Ambul Pediatr 2005;5:122-6. – “Most families like using computers and feel comfortable using the Internet regardless of socioeconomic status. Fears about the digital divide’s impact on the attitudes of parents toward computers or their comfort using the Internet should not be seen as a barrier to developing Internet-based health interventions for a pediatric clinic population.”

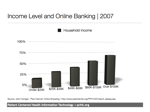

A more sensitive indicator of patient access to electronic health records is likely to be online banking (see this post on that topic), because online banking requires confidence and convenience as well as access to be successful.

Online banking use and income level, from Online Shopping, Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2008

Online banking use and income level, from Online Shopping, Pew Internet & American Life Project, 2008

East Boston Community

Patient-centered HIT applications do not necessarily require use of a computer on the consumer’s end. For example, a mobile phone may be the most effective vehicle for certain populations, whether the information coming to them is in the form of an automated phone call (which can be delivered in multiple languages), a text message (such as for medication reminders), or a more sophisticated combination of audio, graphics and video. A variety of strategies are profiled in a recent report published by the Georgetown Health Policy Institute’s Center for Children and Families (see Health Information Technology: Innovative Applications for Medicaid).

Outside of patient access to computers or the Internet, there are opportunities

Some analysts shortchange vulnerable populations by suggesting that language barriers, the digital divide, or health literacy pose insurmountable obstacles to effective PHR adoption. Perhaps no population faces a greater panoply of barriers–including Spanish as primary language, health literacy, access to computers and the Internet, geographic challenges, and a lack of care continuity–than migrant farm workers. The tool, MiVia, has demonstrated that PHRs can be effective tools when appropriate accommodations are made, such as using community health workers to help facilitate PHR adoption.

As we consider patient-centered health information technology, the definition should be broadened beyond personal health records, to any technology that provides the benefits and impacts of patient access. These impacts accrue whenever the health system is accountable to those it serves, by providing them the information they generate about them, whether in paper, computer or smart card form.

Unresolved issues

- It is unclear how pervasive the conventional wisdom of the “digital divide” is, and if there are related factors that would bias toward inaction even if the data were better understood for populations studied (ethnicity, income, education)

- For populations that are less well studied (e.g. lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, returning soldiers), the impact of provision of access to PCHIT in safety net environments is also unknown. With limited funding available to study sexual minority populations, for example, disparities may only be exacerbated in an environment of HIT without PCHIT.

Countermeasures

In 2008, we are emphasizing safety net providers and vulnerable populations in PCHIT work. We are providing the technical assistance of a knowledgeable medical informaticist and patient empowerment advocate to demonstrate the impact of PCHIT in a vulnerable population. We would also like to spend some effort in packaging this data and presenting it in leadership forums. Ted Eytan did this recently for the District of Columbia Primary Care Association, where it was well received (see Presentation to DCPCA, December 18, 2007), as well as on a recent event at Urban Health Plan, in Bronx, New York (see: “We did it! Thanks Affinity Health Plan and Urban Health Plan!“)

Ways to Engage

In addition to working with health care and IT leadership on promoting PCHIT as part of HIT, it would be valuable to engage with patients themselves. In 2008, we are hoping to shadow a patient who is part of a vulnerable population as they manage chronic disease. This will most likely happen on our trip to Sonoma, California, in March, 2008.